Thomas Hart Benton (1889 - 1975)

Paintings

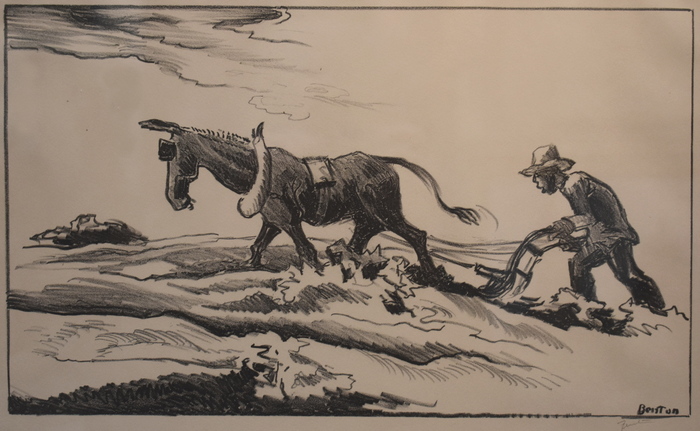

- Thomas Hart Benton

- (1889 - 1975)

- Missouri, Massachusetts, Kansas Artist

- Size: 8 x 13.5

- Frame: 15.25 x 20.25

- Medium: Lithograph

- 1934

- "Plowing"

- View details

- Contact for Price & Info

Biography

Thomas Hart Benton (1889 - 1975) Missouri, Massachusetts, Kansas Artist

Likely the most important painter of the American Scene* movement,

Thomas Hart Benton created a style and addressed subject matter that

was uniquely American as well as specific to his state of Missouri, and

that combined elements of modernism and realism. His signature

painting was regionalist* genre, especially laboring figures. In

addition to many murals, he also painted landscapes and portraits.

Benton

was a highly intelligent, energetic, flamboyant, pugnacious and hard

drinking fellow, who quite often found himself in the center of

controversy. As a student, he was unruly and alienated many of

his peers and teachers.

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Neosho,

Missouri, and named for a great uncle and early United States

Senator. His father, Colonel M.E. Benton, was a Congressman for

eight years, and during the winter, the family lived in Washington D.C.

and in Neosho in the summer. At age 17, after the family had

returned to Missouri, he took a summer job as cartoonist on The Joplin American. Determined to pursue his talent, he later said he had to run away from home to become an artist.

In

1907-1908, he studied with Frederick Oswald at the Art Institute of

Chicago* and then studied in Paris for three years including briefly at

the Academie Julian* under Jean-Paul Laurens and for a longer period at

the Academie Collarossi*, where he could work independently.

In

1911, Colonel Benton decided he could no longer support his son in

Paris, so Tom went to New York. Between 1910 and 1920, he

experimented with styles of Impressionism*, Neo-Impressionism*, Post-Impressionism*,

and Synchromism*, the last influenced by his friend, Stanton

MacDonald-Wright. For much of this time, he was a dedicated

modernist, but a fire destroyed most of the examples of his painting

from this time period.

"His draftsman experience in the Navy, 1918-19, led to his American Scene realist style beginning with his circa 1921 West Side Express. That recently-surfaced masterwork painted for the educator Caroline Pratt, led to many ciryscapes and the never-commissioned 17-panel mural project that he titled, The American Historical Epic (1922-27 ).

He set aside the "Epic" to travel America for two years collecting drawings. He had already completed his research when Alvin Johnson commissioned his America Today murals (1930-31) for the New School for Social Research* in New York City. This ground-breaking work (now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) earned him much respect and many important mural commissions. Its fame was key to the support of artists in the Federal Art Projects.* (McCraw)

His murals at the

Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City are major American Scene

murals, and in 1957, he was commissioned by Robert Moses, chairman of

the board of the Power Authority of the State of New York to paint a

mural for the Power Authority at Massena.For this work at the

site, he did extensive research on the theme, which was the Canadian

expedition of Jacques Cartier in the mid 1500s.

The early part

of his career he lived in New York City where he taught at the Art

Students League* and became a major influence on the style of gestural*

painter, Jackson Pollock. But increasingly Benton grew to believe

that art should express one's surroundings rather than abstract ideas

and that the ordinary person most exemplified American life. Many

of these ideas he inherited from his Populist father who served as a

Congressman from Missouri from 1897 to 1905.

From 1935, he established a studio in Kansas City from where he painted for the next forty years until his death at age 85.

He

was both a prolific lithographer, completing 80 lithographs* between

1929 and 1945, and writer including two autobiographies, An Artist in

America, and An American In Art. Fellow Missourian and former United

States President Harry Truman said that Benton was "the best damned

painter in America."

Source:

Matthew Baigell, Dictionary of American Art and Thomas Hart Benton

BENTON, THOMAS HART

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri on April 15, 1889. Even as a boy, he was no stranger to the "art of the deal" or to the smoke-filled rooms in which such deals were often consummated. His grandfather had been Missouri's first United States Senator and served in Washington for thirty years. His father, Maecenas Benton, was United States Attorney for the Western District of Missouri under Cleveland and served in the United States House of Representatives during the McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt administrations. Benton's brother, Nat, was prosecutor for Greene County, Missouri, during the 1930s.

As soon as he could walk, Benton traveled with his father on political tours. There he learned the arts of chewing and smoking, and while the men were involved in their heated discussions, Benton delighted in finding new cream colored wallpaper on the staircase wall, at the age of six or seven, and drew in charcoal his first mural, a long multi-car freight train.

As soon as he was eighteen, even though his father wanted him to study law, Benton left for Chicago where he studied at the Art Institute during the years 1907 and 1908. He continued his studies in Paris, where he learned delicious wickedness, aesthetic and otherwise.

Once back home, he became the leader of the Regionalist School, the most theatrical and gifted of the 1930s muralists and as Harry Truman described him,"the best damned painter in America."

Detractors said that Benton was "a fascist, a communist, a racist and a bigot"; the ingenious structure, powerful use of modeling and scale and the high-colored humanity of the murals and easel paintings are retort enough. He was a dark, active dynamo, only 5 ft., 3 1/2 in. tall. He was outspoken, open, charmingly profane; he had a great mane of hair and a face the texture of oak bark. He wore rumpled corduroy and flannel, and walked with the unsteady swagger of a sailor just ashore. He poured a salwart drink, chewed on small black cigars and spat in the fire.

Benton was once described as the "churlish dean of regionalist art." If you listened to a variety of art authorities, you would find them equally divided between Harry Truman's assessment of Benton as "the best damned painter in America" and Hilton Kramer who proclaimed Benton "a failed artist."

The East Coast art establishment tended to regard Benton as memorable for one reason only: he was the teacher of Jackson Pollock.

Benton was married in 1922 to Rita, a gregarious Italian lady, and they had a daughter and a son. At the height of his fame in the 1940s, Benton bungled the buy-out he was offered by Walt Disney and went his own way, completing his last mural in 1975 in acrylics the year of his death.

He died in 1975.

Sources:

LA Times, Book Review section of Sunday, November 26, 1989

M.Therese Southgate, MD in the Journal of the American Medical Association;

John Garriety in Connoisseur Magazine, April 1989

Jules Loh, "Unforgettable Thomas Hart Benton", in Reader's Digest

Compiled and written by Jean Ershler Schatz, artist and researcher from Laguna Woods, California.Addendum by AskART. Benton scholar Fred McCraw wrote

that "Benton was not a grandson of the Senator. He was a Grand Nephew.

(Email to AskART, 5/2015)

Dorothy Miller Remembers Thomas Hart Benton (1985)

Interviewed by Jessie Benton Evans

Copyright by Jessie Benton Evans

In

a recent interview with Dorothy Miller, affiliated with the Museum of

Modern Art as assistant to Alfred Barr, and curator of painting and

sculpture during its formative years, Miller offered another view of

Thomas Hart Benton.

"During a brief period in the early

thirties my husband and I used to visit Thomas Hart Benton in New York

City. He lived on 13th St. in a big studio with a very nice Italian

wife (Rita). He was a friendly, nice guy. They would have 16-20 people

over, feed us, while he played the harmonica and his wife played the

guitar and sang, everyone having a jolly time. He was terribly nice and

amusing.

"My husband, Holger Cahill, ran the W.P.A. eight years

during the Roosevelt administration. He knew Benton very well and

hundreds of other artists. In 1932-33, Holger ran the Museum of Modern

Art during Alfred Barr's illness... he was so overworked he couldn't

sleep. My husband finished a big American art show with work from

1862-1932. It was the only time Whistler's Mother came back from the

Louvre. Holger put Benton in the show. I remember Benton saying, "Look,

you don't have to put me in this show just because we're friends." But

he deserved to be in it. He was becoming famous.

"We were going

to New Mexico and said, 'Let's stop off in Kansas City and see Benton'

(the artist had left New York City in 1935). It must have been the

early 30's (sic). He was living in a very contemporary suburban-type

house. His wife was just as nice as before. She said, 'Come on over for

dinner.'

"He was a totally changed man, totally a nasty guy,

apparently because of his early success then being forgotten. His

paintings were the same in style, only bigger. We stayed for dinner and

his wife did all she could to make it a success. He was so

disagreeable. I think my position at the Museum of Modern Art had a lot

to do with his attitude; and Holger had sponsored modern art for the

W.P.A. (Benton had questioned the validity of modern art and been

severely criticized for doing so, in addition to losing his leading

position in the art world with the rise of modernism.)

Source:

Jessie Benton Evans (the younger)

Biography from Spanierman Gallery (retired)

Thomas Hart Benton, along with his contemporaries Edward Hopper, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry, was one of the key chroniclers and interpreters of American life from the late 1920s through the mid-twentieth century. His compositions embody the rushing energy of America during the modern era, celebrating the country's land, history, people, strength, and beauty.

The son of Congressman Colonel Maecenas Eason Benton and Elizabeth Wise of Neosho, Missouri, and the great-nephew and namesake of the celebrated U.S. Senator from Missouri, Benton was born and raised in the rural Ozark town of Neosho. From 1896 to 1904, the family lived in Washington, D.C., where his father represented Missouri in the United States Congress.

Benton's artistic precociousness was apparent by age five, when he began to draw Indians and railroad trains, subjects that he frequently included in his later works. As a young boy, he executed what he considered to be his first mural, drawing in crayon on a freshly papered staircase wall.

Benton's exposure to art during grade school visits to the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Library of Congress encouraged him to enroll in formal art classes at Western High School in Georgetown and then, in 1907, to study at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Determined to pursue art as a career, in 1908 Benton departed for Paris where he attended the Académie Julian. During his Parisian sojourn, Benton devoted time to studying art at The Louvre, where he was inspired by the work of the Italian Renaissance and Spanish Masters, El Greco in particular. Although he experimented with both Academic and Pointillist styles, Benton fell under the spell of works by the French artists Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. He was also mesmerized by the art of his friend and fellow-American, the Synchromist artist Stanton MacDonald Wright. By the time of his return to Missouri in 1911, Benton was a fervent Modernist, painting in the Synchromist style.

After eleven months at home in Neosho, Benton moved to New York City. From 1912 to 1918, he worked as a commercial artist, ceramic painter, set designer, gallery director, and art teacher. In addition, Benton was engaged as an historical reference and portrait artist for the fledgling motion picture industry, which was located across the Hudson River in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

After enlisting in the U.S. Navy in 1918, Benton was stationed at the Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia, where he poured over books on American history, and sketched while off duty. Although some of these pencil drawings and watercolors were semi-abstract, most focused on the activities of the people in his immediate surroundings. These drawings, exhibited to acclaim in 1919 at the Daniel Galleries, New York, were seminal in his career; they were Benton's first images focusing on the American scene.

Motivated by his interest in the progression of American history, between 1919 and 1924, Benton created his first series of paintings, The American Historical Epic (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri). His signature style emerged in these works -- energizing figures with colors applied in a stipple-like manner, he portrayed pulsating forms personifying the constantly changing, dynamic experience of American life. The realistic subjects and motifs in these paintings reveal Benton's break from Modernist abstraction.

The decade from 1925 to 1935 was one of intense artistic activity for Benton. While teaching at the Art Students League in New York, he executed numerous murals, some portraying historical themes and others depicting contemporary urban and rural events. America Today, 1930, Benton's first large-scale mural painted entirely in egg tempera, was produced for The New School for Social Research, New York; The Arts of Life in America, 1932, was commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art for its library (now, Collection of the New Britain Museum of American Art, Connecticut); A Social History of the State of Indiana was painted for the Indiana State Pavilion at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair (now, University of Indiana Auditorium, Bloomington); and A Social History of the State of Missouri, 1935-1936, was executed for the Missouri State Capitol Building, Jefferson.

Benton returned to Missouri in 1935 to complete the State Capitol mural and to assume the helm of the Painting Department at the Kansas City Art Institute. He and his family continued to summer at Chilmark, on Martha's Vineyard, where from the early 1920s he had maintained a home and studio. Benton also proceeded with his annual practice, begun during the late 1910s, of trekking through the back roads of America to create pencil sketches representing the various rural regions and people.

Benton's working method involved laying out his designs from pencil sketches created on his travels, and applying pen and ink over some of the details to define and preserve them. He next formed a three-dimensional clay model or maquette that resembled a stage set, and painted, arranged, and then studied its clay figures and adjunct details (such as trees, leaves, rocks, etc.) The completed maquette served as the prototype for oil and tempera studies, and for the subsequent fully realized compositions. Benton destroyed most of the maquettes after use, but of the few to survive as a model for Turn of the Century, Joplin (The Benton Trust), a mural Benton executed in 1971 for the Municipal Building in Joplin, Missouri.

It was during Benton's participation in a 1934 exhibition with Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry at Ferargil Galleries in New York, that critics coined the term "American Regionalism" or "American Regionalist School." Although there was no such "school," response to the show by art reviewer Thomas Craven and others catapulted the trio of Midwestern artists to national attention. Time Magazine featured a Benton self portrait on its cover and included an article on the "New American Art." Benton, however, felt the designation too confining since he "was after a picture of America in its entirety."

Benton authored many books and articles on art and current events. In just one year, 1937-1938, he published Artist in America, his best-selling autobiography, and wrote and illustrated articles for Life Magazine, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, The Kansas City Star, and Scribner's Magazine. In 1938, he also began a series of lithographs on the American scene for Associated American Artists of New York.

During his lifetime Benton produced over 4,000 works. The majority of his paintings are now in museum collections, including San Francisco's California Palace of the Legion of Honor and The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; New Britain Museum of American Art, Connecticut; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence; Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland; Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; St. Louis Museum of Art, Missouri; Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska; Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska, Lincoln; The Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey; The Brooklyn Museum, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, New York; Canajoharie Library and Art Gallery, New York; Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Tennessee; Hunter Museum of Art, Chattanooga, Tennessee; Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, The University of Texas, Austin; Randolph-Macon Woman's College, Lynchburg, Virginia; The Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia. Benton's works are also found in many other public and private collections.

SKF

© The essay herein is the property of Spanierman Gallery, LLC and is copyrighted by Spanierman Gallery, LLC, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Spanierman Gallery, LLC, nor shown or communicated to anyone without due credit being given to Spanierman Gallery, LLC.

Thomas Hart Benton

Born: Neosho, Missouri 1889

Died: Kansas City, Missouri 1975

Important realist painter of the regional school, muralist, printmaker, teacher, writer

A member of the famous Missouri political family, Tom Benton grew up near the Ozarks. He left at 17 to study at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1906-07 and in Paris at the Julian Academy 1908-11. Back in New York City, he was a professional painter beginning 1912, but he was unable to sell his painting based on European modernism.

In WWI, Benton was an architectural draftsman for the Navy and in this job was forced into realism. At his first postwar exhibition, some of his new paintings sold.

He taught at the Art Students League from 1926-35. During this period, Benton traveled all over the US, sketching in the industrial centers, the South, the Far West, Texas, and New Mexico.

After 20 years in New York City, Benton left what he termed an intellectually diseased lot of painters to return to Missouri as Director of painting at the Kansas City Art Institute.

He has become famous for painting the Contemporary American mural called tabloid art for the New School of Social Research in New York City. When he painted the 45,000 sq. ft. mural for the Missouri State Capital in 1935-36, he rejected customary heroic figures and instead depicted Boss Prendergast, Jesse James, and Frankie and Johnny.

With Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, Benton realistically portrayed the essence of an American region.

Source:

Peggy and Harold Samuels, Encyclopedia of Artists of the American West, 1985, Castle Publishing

Biography from The Columbus Museum of Art, Georgia

The son of a U.S. Congressman and the grandson of a U.S. Senator, it is

no surprise that Thomas Hart Benton was influenced by American politics

and the American scene. He was born in Neosho, Missouri in 1889,

studied at the Art Institute of Chicago before moving to Paris to study

at the Academie Julian for three years.

After working as a naval draftsman in World War I, Benton returned to

New York and started capturing the American scene on his canvases, a

movement that would later be called "Regionalism."

Benton's work

shows elements of the Synchromist movement that advocated that art of

form through color as well as the influence of Michelangelo and El

Greco with his statuesque figures.

Benton and his wife moved to Kansas City in 1935.

Source:

Staff, Columbus Museum

Addendum . Benton scholar Fred McCraw wrote that "Benton was not a grandson of the Senator. He was a Grand Nephew. (Email to AskART, 5/2015)