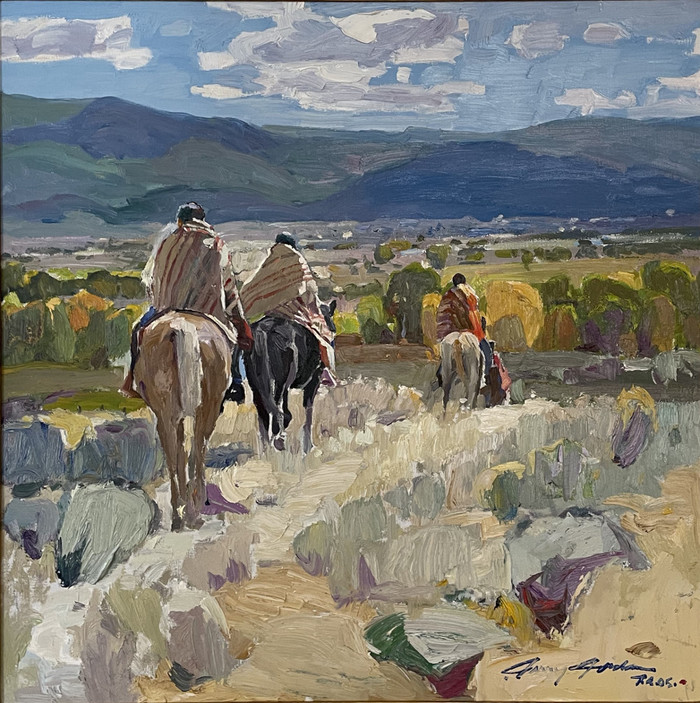

Jerry Jordan "The People of the Valley"

- Jerry Jordan

- Born 1944

- Taos Artist

- Image Size: 30 x 30

- Frame Size: 40 x 40

- Medium: Oil

- "The People of the Valley"

- Contact for Price & Info

- View All By This Artist

Details

Although very indistinct, in the center of the painting is the Millicent Rodgers home. Now a Taos Museum.

This painting will be included in a book that will be published later this year.

Western, Cowboys, Indians, TaosBiography

Jerry JordanBorn 1944

Partway through a blue-corn enchilada in the bright courtyard of a cafe in Taos, New Mexico, Jerry Jordan leans back, looks up, and points randomly to a worked tin fight fixture on a shaded adobe wall. "That's lavender, " he says. "It's lavender and blue. It's not gray. If you paint it gray, the painting's boring. "Jordan shifts his gaze, squints, and in a moment has identified two more subjects: not a group of people eating, but "that pink blouse, " and a play of light and shadow; not a cafe umbrella, but the translucent orange shape of it seen from below, with the inverted "blue bowl of the sky" above, and the umbrella's contour of corded piping-pure purple." "See that?" he says, and whistles softly. "Fantastic!"

Like many artists living in Taos or its environs, Jerry Jordan has spent much of his life elsewhere. Born in 1944, he was raised on a farm in Texas. He ruefully admits that his first painting was painted by numbers, at age fourteen. Two years later, during a family reunion in a park in Paris, Texas, he "roamed into" the adjacent studio of the painter W. R. Thrasher. With dry humor Jordan delights in retelling the story of how this chance encounter with a successful artist awakened his own professional ambition.

"He had twenty, thirty paintings there- seascapes, still lifes, trees, roads, [every kind of subject]- and I was totally fascinated, just blown away, that anyone could do that," Jordan says. "Seeing that much art at once just captivated me?

"I asked Mr. Thrasher while I was there, would it be possible for me to come here during the summer and stay a little while and watch you paint?' And he said no, and didn't think long about telling me no, either. I said, 'Well, why not?' And he said, 'Well, I don't teach.' I said, 'Well, you could make an exception. ...'And he said, 'I don't make exceptions and I don't teach.' So, I said, 'Well thank you.'

"I got home and wrote him a letter and said, 'Mr. Thrasher, to reiterate, I am interested in becoming [your] student, and I'm really sincere about [wanting to become] a painter.' I sent him the letter, and he didn't answer. So, about a month later I wrote him another one, and he didn't answer that. I thought, he's probably busy, so I'll give him a little more time. I gave him a little more time, and then I wrote a third letter, and he didn't answer that. So, I thought, I know what it is: he doesn't realize that I really have talent! I'll do a little 12 " x 16 " painting and send it to him, and then he'll know that I can really paint. (I didn't know how to paint.) So, I copied a Robert Wood painting, and sent it with another letter. And he didn't answer that.

"So, I wrote him the fifth letter. (This took a year, see.) And I said, 'Mr. Thrasher, I gave you the benefit of the doubt on the first letter; I thought it could have gotten lost. But, you know, I've gone to the trouble of painting a painting; I've sent it to you; this is the fifth letter, and the least you could have done is written me back and said, 'Son, I am busy; thank you for your painting; you're going to be good, just work hard,' or whatever; but you didn't even do that. So at least send me my painting back. ' "

Jordan chuckles. "I got a letter back," he remembers, "just like that. He said, 'I have never met a young man, as young as you are, with so much audacity, and determination to become a painter. So ... come this summer and spend three weeks with me.' "

During the summers of his junior and senior years in high school what Jordan learned from his mentor was that, from how to stretch a canvas to how to hold a paintbrush, let alone how to treat a given subject, he "didn't know anything." Thrasher said, "Jerry, it'll take you sixteen years to begin to comprehend what I've exposed you to." Jordan recalls his teen-aged reaction: "I thought, Yeah, sure, you don't know how quick I am at this! It was later, one day when I was painting, that I said, 'Oh. That's what he was talking about ... twenty years ago.' It took that long; I was exposed to so much. "

Apart from his early tutelage under W. R. Thrasher, Jordan describes himself as mostly self-taught, and as having been especially influenced by the work of Richard Schmid, Edward Szmyd, and Ray Vinella (one of the so-called Taos Six, a group known for its contemporary paintings of the American West). "But," Jordan adds, "when people ask where I studied, I say 'Paris' (and under my breath add 'Texas')!"

The youthful fervor and perseverance that W.R. Thrasher had observed in Jerry Jordan carried Jordan through some remarkable accomplishments during his earliest years as a visual artist. Still in high school, he persuaded the local school board to let him become "the first entrepreneur self-employed distributive-education student" in the school district's history. That year (1962) he built himself a studio ("exactly like Mr. Thrasher's") on his father's 40-acre farm, and in 1963 sold $4,000 worth of his own paintings.

In 1964, Jordan married his wife, Marilyn, and they moved to Taos, where he was offered the directorship of a gallery. He accepted, thinking he could paint and direct a gallery simultaneously. He found out he couldn't. Still responding with a young artist's insecurity, he also concluded, in Taos, "that everybody could paint except me." He and Marilyn moved back to Texas. But Jordan found that even in his home state the quest for a style distinctly his own wasn't easy.

In 1969, daunted by the critique of a gallery owner in Lubbock, he gathered up all his art supplies and paintings, had a garage sale, locked his studio door, moved to Tennessee, and embarked on an entirely new career-as a musical performer and comedian. With his brother Harweda, Harweda's wife, Colleen, and Marilyn, he formed The Jordans, a "soft-country, soft-contemporary gospel" group, and toured with them for nearly ten years-until 1978. An album released on an MCA label, "Phone Call from God, " won Jordan a Country Music Award: Comic of the Year for 1976.

Though Jerry Jordan still performs with The Jordans, the group no longer "goes on the road, " and for the past ten years he has devoted himself primarily to painting, his "first love. " Settling again in Texas in 1978, he found himself increasingly making visits to Taos. "I don't know why," he says, "you just come to Taos. It's the art, and the art community, and the galleries. I was 'adopted' by an Indian family [the Reynas) at the Taos Pueblo, in 1984 [and painted and lived for a short time with them]. I love the Indians and their way of life; I like the mixed [New Mexico] culture; I like the architecture."

Jordan painted New Mexican subjects when he still lived in Texas; he would come to Taos, make studies, take photographs, go back to Texas, and paint from them. It was not until 1986 that Jordan bought an adobe home on Taos's historical register and with Marilyn and their daughters, Nicole and J'Brenta, moved here permanently.

In assessing his maturation as a painter, Jerry Jordan says that "a natural evolution" toward impressionism has occurred in his work. While he experiments continually with approaches to painting, and while his subject matter is eclectic, his most distinctive paintings are characterized by abstract treatment: "pushed" (exaggerated) color, loose brushwork, attention to texture and light. He paints whatever interests him most-Pueblo Indian subjects, Southwestern landscapes, flowers, adobes, hot air balloons-and he is prolific, producing about 100 paintings per year. He is currently at work on a study for his most ambitious project to date: a triptych composed of three 9' x 12' canvases, depicting nineteenth-century Pueblo Indians in a wooded landscape.

The best of Jordan's work plays with contrast: light and shadow, exaggerated and muted color, soft and angular contour, animate and inanimate detail. His compositional elements often take risks and establish subtle relationships, as in the recent portrait of John Marcus of the Taos Pueblo, titled White Clay Dancer. Here a rough wooden purple pillar could divide the painting vertically in half-and yet doesn't. Instead, it helps to frame the off-center human figure, also erect, who seems, with his age and dignity, to be the support on which his community, like a roof over a pillar, depends.JERRY JORDAN

Living in Taos, New Mexico

Born in 1944, he was raised on a farm in Texas, and as a child became exposed to the landscapes and still lifes of local artist W.R. Thrasher, who became his mentor. Aside from that association, Jordan is largely self taught. He laughingly says that when people ask him where he studied, he says "Paris" and then under his breath adds "Texas." However, he also credits Richard Schmid, Edward Szmyd, and Ray Vinella as strong influences.

In 1962, at age eighteen, he built himself a studio on his father's 40-acre farm and the next year sold $4000. worth of paintings. He married his wife, Marilyn, and in 1964, they moved to Taos, New Mexico, where he became the director of a gallery, thinking he would also have time to paint. But he learned that doubling up was a mistake and he returned to Texas to devote himself full time to his work and to find his unique style. He went through a period of discouragement with his painting, and with his wife, brother and sister-in-law formed a gospel singing group called the Jordans. He toured with them for nearly ten years, and in 1976, he won the Country Music Award, Comic of the Year.

He settled again in Texas but made increasing numbers of trips to Taos, and in 1984 was adopted by the Reynas family at the Taos Pueblo, and he painted and lived with them for a short time. In 1986, he and Marilyn bought an adobe home on the Taos historic register and have lived there with their two daughters. From that time, he has been a successful painter of eclectic subjects including cityscapes, still lifes, and rural landscapes with styles that include Impressionism and Abstraction. He says he paints whatever interests him from Pueblo Indian subjects to hot air balloons. Many of his works are in print editions of American Master Prints, and he completes about 100 paintings a year.

He often explores the play of contrasts, light and shadow, exaggerated and muted color, animate and inanimate detail, soft and angular forms. He "pushes" colors, that is creates combinations that logically would not go together. He says: "I love turquoise. I love purple." He sees them everywhere, and for him those colors transcend literal or local references.

Artist Statement: "Talent accounts for about two percent of a painter's success. The rest is just I'm-a-gonna-do-it determination".